| If the language is not

in tune, what is said is |

| not what is

meant. |

| Confucius |

Did you understand? Probably

not. It can be expressed in language that everybody can understand: "In

a word, there are three things which last for ever: faith, hope and love;

but the greatest of them all is love." (1. Cor. 13 v. 13). This formulation

contains all of the elements of speech, which serve to make it understandable,

since this language is:

| - |

simple |

| - |

short |

| - |

lucid |

| - |

ordered |

| - |

and the words are in common

usage |

The Bible, especially the

New Testaments, is an excellent teaching text for clear, comprehensible

and convincing language.

| top |

|

|

Intelligibility

Intelligibility is a prerequisite

for successful discussions between doctor and patient. The doctor thinks

and lives and moves in his own language which is for him, the expression

of his "reality". However this contains the source of multiple interference's

ranging from simple misunderstandings to complete incomprehension on both

parts. This problem is made worse as the doctor often believes that he

has been understood. It can be totally astounding to later hear critical

remarks from the patient, such as: "The doctor didn't talk to me about

that...", "I really didn't understand what the doctor wanted ...". One

of the best questions to check why discussions later turn out to have been

"unsatisfactory", is: "Did I use language that my patient could start to

understand?"

Intelligible speech

is as much a question of content as of style of speech. Schulz von Thun

described 4 properties of intelligible speech:

| • |

Simple |

| • |

Smooth and ordered |

| • |

Brief and precise |

| • |

Additional stimuli |

What do each of these imply?

Simplicity:

Simple speech uses short

sentences and common words. If technical terms are unavoidable,

they should be explained. Descriptive speech raises the level of

intelligibility. A doctor who talks to his patient like a "normal person"

will be better understood, and be able to motivate the patient better than

one who uses "scholarly" speech.

It is just as difficult to

speak simply as to write simply. In fact repetitious lectures or "double

dutch" fall easily from the lips. However this style is full of pitfalls.

It is likely to maintain an undefined distance from the other, and prevent

real involvement in discussion. It is only unequivocal facts that

can be expressed in simple language. Long-winded speech is often an indication

of vague thinking. Simplicity does not only increase intelligibility, it

also seems genuine, and creates trust.

Smooth and ordered:

These requirements are fulfilled

by language which is transparent from the outside and intrinsically

consequential. Ludwig Reiners said: "A person can not express two thoughts

at the same time: this means that he has to put them one after the other."

What Schopenhauer described about writing also applies to speaking: "Very

few people write in the way that an architect builds, in that he first

makes a plan having considered all of the details. Most write as though

they were playing dominoes."

"Associative speech" is a

typical example. The flow of speech does not depend on thoughts which have

been put together in order, but from coincidences that arise as the person

is talking. Almost everybody tends to use associative speech, which is

certainly not a rare method of speech. Associative speech leads to long-winded

explanations, which rapidly result in the other person losing interest.

Brief and precise:

This brevity applies to language

as well as factual content. Most people have difficulty in expressing

themselves briefly, and it can usually only be attained with practice and

discipline. Even Goethe wrote to his 18-year old sister: "As I haven't

the time to write you a short letter, I am writing you a long one ..."

The telegram is the briefest

form of language, and the aphorism is the extreme of factual brevity. Neither

of these are of course suitable for discussion between patient and doctor.

The style of the telegram has an impersonal effect, and misses the contactive

function of speech. Aphorism can also lead to strain created by concentration

on understanding so much that has been expressed so briefly.

|

The guideline has to

be:

Use sentences with a length and information content appropriate

to the extent to which the patient can take it in and assimilate it.

|

|

Brevity also means that not

too many sentences should follow one after another. Studies have shown

that an untrained listener is unable to easily recall the contents of a

series of sentences which last more than 40 seconds. Brevity also means

giving much information with few words, as well as not too many

pieces of information one after the other.

Brevity should also not be

won at the cost of minimizing contact and self-revelation. Although the

telegram contains highly concentrated information, it is not ideal from

the point of view of information theory.

Elements of a communication

which could theoretically be left out as they contain no additional information,

might appear redundant at first glance. They are however necessary

to support and complement the basic information. Since at least two thirds

of what is said only once is forgotten, a certain amount of "redundancies"

are unavoidable when talking.

Additional stimuli:

Pictures and metaphors in

speech are important supports for the lucidity of what is said. They are

a vital rhetorical stimulus and, as it were, the salt in the soup of information.

Goethe said: "Don't keep metaphors from me or I won't be able to explain".

| top |

|

|

Picturesque language

Most people are "visual". Our

speech is full of pictures, even if we are not always consciously aware

of them: "He jumped at the chance", "She stole a glance at him."

Speaking in pictures and

metaphors is an effective method to make oneself better understood by "plasticity".

Medical language is full of abstract terms, and here in particular, the

use of pictures and metaphors can lead to better comprehension.

The New Testament (and in

German, the Luther translation in particular) is a mine of effective metaphors

and illustrations. The parable of the lost sheep could hardly be better

expressed more pragmatically than in Matthew 18 v. 12: "And what do you

think? Suppose a man has a hundred sheep. If one of them strays, does he

not leave the other ninety-nine on the hill-side and go in search of the

one who strayed?"

This text is also a good

example to show that a statement clothed in a question is a very effective

tool to convince. The New Testament says that Jesus "... only spoke to

them with parables." It had already been said of Him in Psalm 78 v. 2:

"I will open my mouth in parables, I will utter hidden things, things from

of old ..."

There are limits to the extent

to which one can learn to use pictures and metaphors. There are however

two possibilities which one can use in order to make one's style of language

more vivid for the patient.

| 1. |

Systematically

check whether abstract terms could be better explained by a picture

or metaphor from daily speech. |

| 2. |

Consider which

of the pictures you use have proven to be the most effective, and

use them more often in discussions with patients. |

Here is an example from routine

clinical practice:

It is particularly difficult

to convince patients with illnesses unaccompanied by symptoms that they

should be treated. The most common counter-arguments are: "I don't feel

anything ...". "Everything has been alright so far ...". In these cases,

I argue with the following comparison: "What you say reminds me of a man

who fell from the roof of a block of flats, and called out to those in

the first floor: 'I really don't know why men are afraid of falling. Everything

has been great so far!'"

Metaphors as well as examples,

comparisons and the sparing use of quotations, sketches, demonstration

material or cartoons can be further stimuli to increase understanding.

They assist discussion, but should not replace it, and always need explanation.

Doctors themselves probably don't encourage their patients enough

to make themselves better understood by the use of a sketch or drawing.

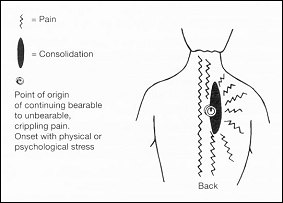

One patient with severe angina pectoris could best describe the pain, which

mainly occurred in the back, by means of a sketch (figure).

The highly symbolic content

of pictures drawn by patients with cancer often allows very real

insight into their condition. Patients with tumors frequently have great

difficulty in finding their real attitude to their illness and in verbalizing

their perception and understanding of it.

The highly symbolic content

of pictures drawn by patients with cancer often allows very real

insight into their condition. Patients with tumors frequently have great

difficulty in finding their real attitude to their illness and in verbalizing

their perception and understanding of it.

Simple pictures and drawings,

even though no great works of art, sometimes allow a staggering insight

into the world of feelings and experience of the patient, who does not

know how to begin to express them in words.

| top |

|

|

The style of speech

Speaking style must take account

of the patient as an individual along with his age, sex, education, job,

social status, role, and cultural group. The actual medical situation has

a specific implication.

Observation of the style

of speech of the patient is of relevance for mutual understanding and

for comprehending his world and the effect on him of the society in which

he moves. Wilhelm von Humboldt remarked many years ago that differences

in styles of speech did not only depend on learning, talents or intellectual

ability, but also on the totality of the person.

The same words can have completely

different meaning depending on the age of the person, as in young people's

speech.

Turns of speech which are

typical for certain groups (and therefore acceptable there) have no place

in conversations between doctors and patients. As modern medicine becomes

more technical, technical terms have tended to appear in medicine such

as "change batteries", "hook you up for a quick infusion" etc.

A further extreme of this

is the excessive "psychologization" of speech, so that for example "goal-orientated

communication with erotic components and tendencies to emotional fixation"

is used instead of "to flirt".

The social reality of certain

groups of people determines the style of speech or code. Code means

a predetermined way and attitude as to how one of the group expresses himself.

Codes are therefore "Sociolect". There are said to be 2 codes:

| • |

Elaborated

code = EC |

| • |

Restricted code

=

RC |

As regards speech behaviour,

EC and RC have the following differences:

| • |

The

language in EC is less stereotypic in its effect, and the way of expression

is more differentiated; |

| • |

It is easier

to express individual points of view and judgements in EC |

| • |

Logical and factual

relationships can be expressed more easily in EC |

| • |

Superiority and inferiority

can be more explicit. |

The various language patterns

can (at least statistically) be classified according to certain social

behaviour patterns:

| • |

RC

is more associated with conventional, status-orientated rather than person-orientated

behaviour patterns. |

| • |

RC tends to maintain

an acquired opinion through thick and thin. |

| • |

RC tends to be

characterized by anxiety rather than guilt. |

| • |

RC has a tendency to be

conservative rather than radical. |

It has been estimated that

90% of the adults in West Germany use an elaborated code. That does not

mean that the remaining 10% should be "down-graded" as using restricted

code. Neither is superior as regards style of speech. Intelligence and

affect can be developed equally in one as in the other. However somebody

who uses an elaborated code, usually soon learns to use a restricted code

as well, whereas the reverse practically never occurs. There is one style

of speech used by many politicians, that the doctor should avoid at all

costs. This is the blathering and long-winded formulation of zero or minimal

information, which leaves the patient with the impression that he can never

get a straight answer.

| top |

|

| previous page |

|

| next page |

|

|

|

Linus

Geisler: Doctor and patient - a partnership through dialogue

|

|

©

Pharma Verlag Frankfurt/Germany, 1991

|

|

URL

of this page: http://www.linus-geisler.de/dp/dp07_language.html

|

|